Medical errors can happen anywhere and at any time. However, these errors may be most likely to occur at transitions, especially the transition from the hospital to home when follow-up care is still required. Says Alicia Arbaje, an assistant professor at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, “Poor transitional care is a huge, huge issue for everybody, but especially for older people with complex needs. The most risky transition is from hospital to home with the additional need for home care services, and that’s the one we know the least about.”

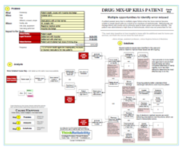

These impacts to the goals become “effects” of cause-and-effect relationships. The Cause Map contains all the cause-and-effect relationships that led to these impacted goals. Causes included in the map are verified with evidence, which can be provided by a variety of sources. Causes can be determined by asking “Why” questions, but more than one cause may be required to produce an effect. In this case, all necessary causes are included and joined with an “AND”.

The patient safety goal was impacted because of a patient’s death due to multiple organ failure when her bone marrow became unable to create blood cells as a result of an overdose of methotrexate. Methotrexate can damage blood cell counts and is primarily used to treat cancer and severe arthritis. The patient was administered a high dose (for methotrexate) of a drug that was not prescribed for her. When the patient left the hospital, the hospital phoned an order for a daily dose of the diuretic metolazone. However, according to court evidence, the order was written down by a pharmacy technician as a daily dose of methotrexate.

Because of the side effects of methotrexate, it is included in a list of eight “high-alert” medications that warrant special safeguards to prevent incorrect dispensing. The typical dose of methotrexate is much lower, usually only once or twice a week. Despite this, the pharmacist missed the error. In a testimony, he was unable to identify a specific reason for this oversight. The pharmacy manager said “there was a breakdown in the system.”

There were more opportunities for this error to be caught before this drug was dispensed to the patient. The patient herself could have noticed the incorrect medication based on the name or information on the enclosed information sheet. However, the patient likely did not fully understand the discharge instructions. Federal data shows that less than half of patients say they’re confident they understand discharge instructions. This patient was also receiving home health care, but neither of the two nurses that saw the patient identified the medication mix-up. Even though a primary purpose of home health care is to develop and follow-up on patient care, a 2013 government report found that more than a third of facilities did not do this properly. Medicare requires that home health agencies verify patient’s medications and check for possible interaction, but inspectors found that nearly a quarter of home health agencies inadequately reviewed or tracked medications for new patients. One of the challenges is that the typical providers of post-discharge patient care (nursing homes, rehabilitation facilities and home health care providers) did not receive any of the funding provided by Congress to upgrade to electronic medical records.

Several systemic issues were identified in this case and actions meant to improve these issues are still ongoing. One reason for increased use of electronic medical records is to avoid delivering prescriptions over the phone, which can result in transcription errors. Ensuring patients better understand their discharge instructions is another goal that could improve patient safety. Lastly, improvements to home health care agencies to ensure their required tasks are being completed effectively is clearly needed, but it has been difficult to determine the most effective way to do this.

To view the Cause Map of this incident, click on “Download PDF” above. Or, click here to read more.